The Early Club Days (Mid-1980s)

With the high demand for Memphis rap cassette tapes, I think it’s important to talk about how, when, and where these tapes were released and distributed.

With the high demand for Memphis rap cassette tapes, I think it’s important to talk about how, when, and where these tapes were released and distributed.

Way back in the earliest days of the developing Memphis rap scene, DJs like DJ Soni D would mix and scratch popular rap singles at Club No Name (aka Club Expo) on Lamar Ave around the mid-1980s. A club operated by Ray The J Nealy. After their sets, it was standard protocol to record these live mixes to cassette and sell them to partygoers leaving the club. This small market was an effective way for both the club and the DJs to generate extra profit and to see what songs worked better than others.

DJ Spanish Fly and the “Oh Word” Era (1987–1990)

DJ Spanish Fly would, of course, famously be forced to take Soni D’s spot in mid-to-late 1987 after Soni D suddenly quit. In an effort not to step on the toes of his fellow DJ, Spanish Fly opted to mix more explicit songs that radio stations typically wouldn’t play. These were tracks from artists like Ice-T, Too $hort, 2 Live Crew, and N.W.A. On top of that, Fly would create breakbeats—extended mixes of one or multiple songs that formed an instrumental-type beat. Showcasing his versatility, Fly would rap over these live in the club, beatbox, and even dance to the grooves he played.

Given how unique this was, Fly’s success was immediate. From about 1988–1990, he sold his cassettes exclusively in the clubs he DJ’d at, essentially beginning his legendary “Oh Word” cassette series around 1988–1989. This series lasted until about 1995 with around 50 different volumes and mixes. At the same time, clubs for younger audiences like 21st Century featuring DJ Jus Borne would get popular locally, showcasing local rap songs.

Expansion of the Scene (1990–1991)

By 1990, the Memphis rap scene had expanded with figures like Gangsta Pat, who was more of a mainstream rapper but still had huge influence locally. Around the same time, Pretty Tony had one of the first big Memphis hits with “Get Buck.” In 1991, artists like Sunny Mack and 8Ball & MJG dropped their debut albums. These singles and albums were now reaching beyond the clubs and could be bought at local record shops like Mr. Z’s and Car Toys. Spanish Fly began selling his Oh Word tapes in stores around 1990 as well, now in larger quantities to meet demand. DJs like DJ B.K. followed suit, releasing their own live and home-recorded mixes on cassette.

Profits & The Rise of Original Production (1991–1992)

The cassette game didn’t become extremely profitable until about 1991–1992. By this point, Spanish Fly was producing his legendary mixes from home and selling them in record stores. According to some, his mixtapes were so sought after that they retailed for up to $20 when brand new. Fly also began slipping in his own productions, such as “Gangsta Walk” on Volume #22 in mid-1991.

DJ Squeeky soon took things a step further, slowly creating entirely original tracks with the help of DJ B.K. at first. Like Fly and B.K., he included popular radio tracks on his tapes, but by late 1992 his legendary “Master Mixtape” series featured more and more of his own work. His breakout came with Volume #4, the first full 60-minute Memphis cassette from a DJ to blow up. It featured tracks like “Skinny But Dangerous” and “Lookin’ For the Chewin,” showcasing local talent like Skinny Pimp, DJ Zirk, and Kilo G. With this release, a new precedent was set.

The Youth Movement (1992–1993)

After the rise of Squeeky and Skinny Pimp, the scene exploded and became accessible to all ages. What was once more of a grown-man game was now being driven by kids buying and producing tapes. Skinny Pimp became the first underground breakout star, performing at schools and high-school parties. Inspired, younger figures like DJ Paul, Tommy Wright, and Juicy J started selling tapes as teenagers, though in the earliest days they were limited to selling inside schools to close friends. This is part of the reason why their earliest volumes are still considered “lost.”

After the rise of Squeeky and Skinny Pimp, the scene exploded and became accessible to all ages. What was once more of a grown-man game was now being driven by kids buying and producing tapes. Skinny Pimp became the first underground breakout star, performing at schools and high-school parties. Inspired, younger figures like DJ Paul, Tommy Wright, and Juicy J started selling tapes as teenagers, though in the earliest days they were limited to selling inside schools to close friends. This is part of the reason why their earliest volumes are still considered “lost.”

By early 1993, Paul, Juicy, and others moved beyond schools, selling in the same places as Spanish Fly, Squeeky, and B.K. From that point on, the scene exploded exponentially.

The Boom Years (1993–1997)

At the height of the Memphis rap tape market—from mid-1993 to late 1997—these cassettes were everywhere. If a store owner was buying them, then the artist would be in there dropping off tapes and negotiating prices. Gas stations, beauty shops, tire shops, barber shops, and even grocery stores stocked a wide variety. When tapes sold out, shop owners often bootlegged their remaining copies to keep up with demand. Of course, this hurt their relationships with artists, but the demand was too high to ignore.

At the height of the Memphis rap tape market—from mid-1993 to late 1997—these cassettes were everywhere. If a store owner was buying them, then the artist would be in there dropping off tapes and negotiating prices. Gas stations, beauty shops, tire shops, barber shops, and even grocery stores stocked a wide variety. When tapes sold out, shop owners often bootlegged their remaining copies to keep up with demand. Of course, this hurt their relationships with artists, but the demand was too high to ignore.

During this period, tapes began spreading outside of Tennessee, reaching Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, and Mississippi. Bootlegs became the standard if you weren’t lucky enough to grab originals. Artists like Skinny Pimp even opened their own record shops like the Gimisum Dungeon, where they would bootleg and sell popular tapes themselves. Skinny Pimp beefed with Tinimaine for bootlegging his 19 Tiny 5 release, while Tinimaine admitted to bootlegging Lady Bee’s Something for the Streets 2 and Gimisum Family 2.

Distribution Expands Beyond Memphis (1995–1997)

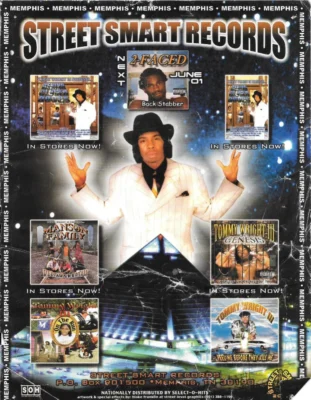

In 1996, Tommy Wright III famously opened a call-in line for mail-order tapes, allowing anyone in the U.S. to purchase Street Smart Records bootleg tapes. I personally knew people in Minnesota who ordered directly from Tommy Wright in 1997. My dad even recalls a transfer student from Memphis arriving at North High School in Minneapolis in 1995 and putting him onto Koopsta Knicca’s Devil’s Playground—a perfect example of how prized these tapes were and how far they traveled.

Even big names like DJ Paul were known to bootleg their own releases, like For Da Summer of ’94 and Lil Fly’s From Da Darkness of Da Kut, well into the late ’90s.

The Decline and Collector Era (1999–2010s)

After the tape scene fizzled out locally around 1999, sites like Mtownbound.com continued pressing bootlegs in the early 2000s, while eBay became the hub for early collectors like MemphisRewind.

After the tape scene fizzled out locally around 1999, sites like Mtownbound.com continued pressing bootlegs in the early 2000s, while eBay became the hub for early collectors like MemphisRewind.

Notably, artists like Player 1 of DJ Sound’s Frayser Click and Tommy Wright III created their own eBay pages, repressing and selling tapes from their collections. This is how many collectors in the 2000s and 2010s acquired the bulk of their tapes.

Legacy

Now, whether you’re listening on YouTube, Spotify, or cassette, one fact remains: Memphis rap is an incredible, short-lived genre born out of a desire to be expressive and different. Most artists made these tapes for their friends and neighborhoods, yet 30 years later someone like myself is dedicating time daily to preserving it.